“Do you think I’m going to Hell?” she asked us - not with defiance, or as if daring us to give any answer in particular. It felt open-ended - curious, almost, to know. This was an evening conversation after tea where the party was majority Christian. But our questioner had stopped attending church many years ago, and her exact frame of mind about it all was uninterrogated in the way it usually is in family life, where a well-meaning, awkward policy of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ is in effect. But that evening, conversation had been nudged by her in the direction of faith, religion, and the question of our final ends.

I don’t think she asked with indignation, but she knew the power of framing the question in that way, at least. Hell. The big ‘H’ - oh man! And what could we say? It felt akin to the subtle lawyer’s ‘and when did you stop beating your wife?’ trick, in which the jury, either way a defendant answers, is left to sift through interpretive ambiguities that prevent a sense of closure on the matter. Aware that what was at stake here was probably someone’s capacity to know the love of God in Jesus Christ, some of the more Protestant-minded members among us that night were happy to launch onto the theme of an ‘mediaeval, religious mindset’ (for which, read ‘catholic’) that cared more about gatekeeping, and giving people chores to perform to ‘get in’. But Jesus had really come to initiate direct relationships, and freely offered grace, and none of that exclusionary talk. While this actually left the details fuzzy on Hell (a doctrine which, no doubt, they were committed to on the grounds of biblical fidelity), this big picture headline was no doubt felt to be a good and healing point to push - a salve to this girl’s wounded sense that we Christians felt ourselves to be better than her; to presume ourselves in the judgement seat. For my part, I sensed that such apologetic gambits, far from making her more attracted to the Christian faith, actually repulsed her. She felt them to be dishonest, in some way, I think. If this God is so tenderhearted and open-armed, then why did his Church get it so wrong in the first place, and torture the consciences of so many in the process? And even if he offers salvation on such generous terms - requiring only this intellectual assent to an idea about Jesus - then doesn’t that make the schema all the more arbitrary and perverse, given its geographic particularity? Good, virtuous people, by dint of growing up in the Amazonian rainforests and therefore without access to this body of notions about Jesus Christ, are to be condemned eternally, are they?

This essay is about what Christians have traditionally said when a nonbeliever asks: “Am I going to Hell?”. I say ‘traditionally’ with some chutzpah, because the presence of many possible responses that mutually exclude one another might be said to defy any overly neat identification of a single ‘tradition’. Infernalism - the view that some will go to eternal conscious torment - can hardly be placed next to a hope for apokatastasis, the view that all shall be called heavenward in the end, perhaps even the Devil himself. But I note that, even for arch universalists like David Bentley Hart, there is something called ‘tradition’ alluded to, if only as an object of ridicule and contempt. For what Hart says is: to Hell - so to speak - with tradition about Hell! His work, outlining what he holds to be the logical impossibility of Hell if the Christian God is who He says He is, with an alternate interpretive view of the biblical texts pressed into service to keep things ticking over, gamely admits it is at odds with “just about the whole Christian tradition” (That All Shall Be Saved, 2019, p. 81). So, an excavation of the main lines of this ‘tradition’ will be my business now, but leaving aside self-declared alternatives like Hart’s.

No understanding of Hell as conceptualised in the West can avoid Dante. In his Commedia, the speaker tours the deepening circles of the abyss, and has many moments to reflect on the comparative levels of justice meted out to its inhabitants - the speaker’s guide, Virgil, provides a moment of awkwardness here, as Virgil explains his own fate in the first rung to the narrator: “without hope we live in longing” (sanza speme vivemo in disio, Inferno iv. 42). But why this limbo - a word meaning ‘hem’ - for the noble wordsmith? Why must so rare a spirit be made to dwell in a kind of netherspace, where they are not tortured per se, but must eternally despair of what they cannot attain, along with other such luminaries as Homer and Socrates? Their fault, as Virgil puts it here, is simply that they lived before Christ. There are also those in Limbo who were geographically separated from Christendom - Saladin, the great Muslim leader who ended Christian occupation of the Holy Land in the 12th century, resides there too. For Dante, clearly, the gap between natural goods (virtues available to all men, including pagans) and the supernatural is decisive. Virgil’s agony is to have to explain, in the manner of a tour guide, the circumstances of his own inalterable stagnation in Limbo, to an audience who will be able to ascend to the zenith of paradise itself.

Dante’s answer to the issue of the virtuous pagan - and sub in for this clanging, old-world phrase of ‘virtuous pagan’ something like ‘people who do good despite not being devout Christians’ - seems rather blunt. Faith in Christ is absolutely necessary for beatitude, and no amount of virtue can overcome that deficiency. And so millions - nay, billions - are shuffled into the hellmouth, charitable, kind and godfearing, but unlucky enough to be born under Seljuk rule, or before 33AD. But it is worth saying that Dante’s is only one take on a difficult internal debate Christians have had about the salvation of nonbelievers, and even his is a softened one in many respects. For though we may find Dante almost psychotically calm about the eternal torment of good people by a just God, his is an interpretation which tries to make sense of Christian primacy in a way that allows him to admire the ancients, and even hope for their eternal fate to be mitigated in some way. It must also be borne in mind that, for Dante, Church and world are one reality - God has claimed the West for his own, by the means of being the official religion of a world empire. A feeling of election possibly leads Dante to justify the suffering pagans as benefiting his own time and place as a theodicy all of its own. As John Marenbon puts it:

The apparent injustice, however, is a sign which leads to faith, since it shows how there are two separate spheres, of earthly and heavenly values, and that the heavenly ones are not comprehensible from within the other, earthly sphere (2015, p. 95)

And so Virgil leads Dante’s fictionalised counterpart with a lamp - but a lamp held behind him. He will, as it were, lead others to the light, but can never be drawn into it himself.

But this is just one spear in a forking that occurs on the Hell problem in Christian thinking, and I sense St Augustine at its base. His is the most coherent - but perhaps most bleak - take on the logic of salvation ever articulated. In the early 5th century and in the last decade of his life, St Augustine was still smoking out his old idée fixe Pelagianism, and an incomplete work, Contra Iulianum, sees the Doctor of Grace pushed to the rather grim conclusion that those before Christ were not really able to be virtuous at all: “God forbid there be true virtues in anyone unless he is just, and God forbid he be truly just unless he lives by faith” (Book IV, ch. III). Perhaps he overstated his case here; after all, he was going toe-to-toe with Julian of Eclanum, a gnarly remnant of a heresy he may have thought he had put to bed almost ten years ago. But he nonetheless provides crisp argumentation to underscore the rhetorical flexing - virtues are so defined by their final ends, and a pagan without the One True God cannot possibly have the correct end in sight; a nonbeliever cannot will the good without proper orientation to absolute Good. Faith is essential to the correct ordering here that makes charity, and salvation, possible.

And to be fair to him, he had some launching-off points in St Paul to confirm this trajectory. Citing Romans 1:22, he contends with Julian that the pre-Christian hordes of antiquity were blinded by pride: “being wise, they became fools”. Elsewhere, the Apostle will suggest rather enigmatically that it is possible to give away all that we have to the poor, or be obliterated in martyrdom, without true charity (in Greek agape, rendered in Latin as caritas, ‘love’) in 1 Cor 13:3. Our relation to God and neighbour has to be in this perfect interlocking called charity, but existing in that state of play is not always readily discernible. It floats free of externals that seem, to our fleshly eyes, good enough displays of virtue, but which mask some fundamental lack. Fittingly by adapting some of St Paul’s words, St Augustine seems to chase the conclusions down a little further though: “Christ died in vain if men without the faith of Christ through other means or power of reasoning may arrive at true faith, at true virtue, at true justice, at true wisdom” (ibid.).

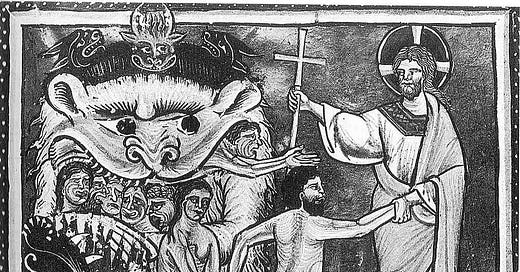

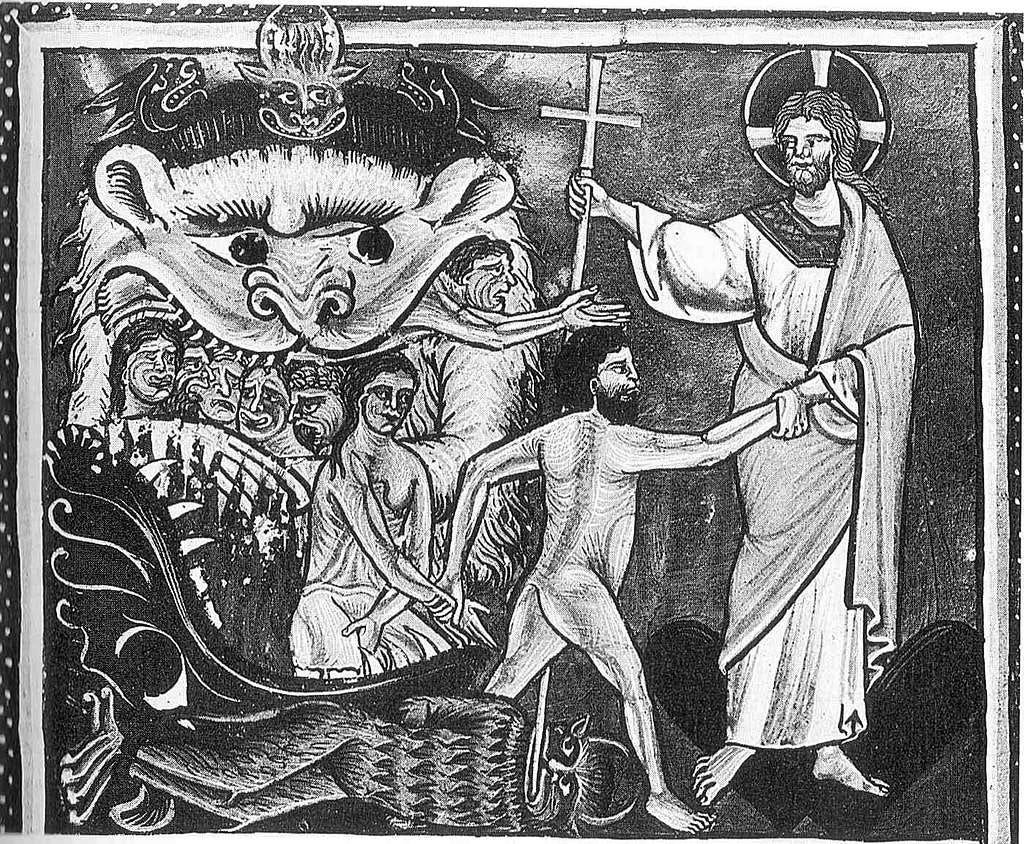

St Augustine begins a tradition which swallows a rather difficult pill in order to be able to maximally assert Christian truth as necessary to salvation. But all those who do not possess saving faith, we must conclude, are damned to Hell. Mind you, St Augustine has to let up this unrelenting syllogistic pressure in a few places though - he is compelled by obedience to sacred tradition to hold that Christ ‘descended to Hell’ in the Nicene Creed, and to honour a cryptic Scriptural passage which holds that Christ “went to preach to the spirits in prison” (1 Peter 3:18). But what on earth for, on his uncompromising view? Either they had saving faith, or they didn’t. And in a letter to Evodius (Letter 164, 414 AD), he is evidently trying to mull it over, and tries on many views to see which one will best settle into his predestinarian system: “You perceive, therefore, how intricate is the question… and also the difficulties which prevent me from pronouncing any definite opinion on the subject” (ch. IV). He is prompted to take unusual interpretive strategies, including the idea that Hell must have different regions - this gets him off the hook, as Christ can descend to ‘Abraham’s bosom’, not Hell proper, to save the first man Adam, and perhaps a few others who may have been given a proleptic awareness about Jesus: Abraham himself, for instance.

At the very least, St Augustine respected the philosophical insight of the great pagans - Plato, for example. Even this represents a minor qualification in a rather wholesale condemnation of the virtues of antiquity, a lip service abandoned by others within his tradition of teaching about Hell. The Reformed stream pays its homage here, and takes it forward with gusto. In the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Protestant Church of England, found at the back of the Book of Common Prayer, we have in Article XIII the difficult view that

WORKS done before the Grace of Christ, and the inspiration of His Spirit, are not pleasant to God, forasmuch as they spring not of faith in Jesus Christ… yea, rather, for that they are not done as God hath willed and commanded them to be done, we doubt not but they have the nature of sin.

Not all points correlate on this Protestant anti-pagan trend, however. Again I turn to the poets, for perhaps poets, in their unsystematic way of doing theology, can better express the hope of God’s mercy even where they hold to a quite tightly constructed soteriological framework. John Milton, arguably England’s greatest epic poet, lives out a great tension here. Milton found shades of truth in the writings of Nonchristians:

“What the sage Poets taught by th' heav'nly Muse,

Storied of old in high immortal verse”

(Comus ll. 514-5)

And his major work closely follows the style of those great poets. But as Neil Forsyth has shown quite convincingly, the whole use of classical epic form in the poem is precisely to denounce the verse of antiquity as temporary, now superseded by the arrival of a superior type of narrative. Adam learns about the coming of Jesus Christ in Paradise Lost, instinctively thinking of him as a military leader, set to defeat Satan like a conqueror. But Milton’s angel guides correct Adam, and show that this will be a different sort of tale - Christ will rule through love and intellectual transformation: “Adam learns he is a Christian hero in a classical poem, and needs gradually to learn the difference, as does the reader” (Forsyth, 2000, p. 518). Christ is not merely a better literary take on the ancient hero or demigod persona, and Milton thereby gets to express qualified respect for his ancient forebears. Firmly within this Augustinian-Danteian tradition, he must also come up against difficult thoughts about the ways of God: if God causes all things, and faith is the only means of attaining the good, then his deliberate withholding of faith from the pagans positions God as the author of evil:

A universe of death, which God by curse

Created evil, for evil only good

(Paradise Lost, II, ll. 622-3)

Being able to make a claim like this is not unthinkable on the Reformed theological schema, but it certainly would have been a consolation to Milton to have a Protestant Bible like the Authorised Version, in which God’s inventive scope in Isaiah 45:7 includes an astonishing rendering: “I create evil”. That the underlying Hebrew (ra’) of course can mean ‘trouble’ or ‘woe’, rather than the philosophical concept of ‘evil’, was surely an oversight of the King James translation team, but a Scriptural tag, however comforting to the Reformed biblicist in the short term, cannot stave off concerns indefinitely about what this would mean for speaking meaningfully about God’s goodness. Rather, ‘good’ comes to be an arbitrary decision of the Divine Will. Milton, like many Reformers, has to take refuge in this kind of voluntarist monism as the only veto against the charge that God unfairly consigns so many to damnation - all things collapse into the eternal will of God in a way which denies every created thing any realistic sense of autonomy. Calvinistic double predestination is the organic corollary - God wills a clan of the elect to permanent beatitude, and the rest to the pains of Hell, forever. But on a certain view, that is at least a clean theoretical system, if loathsome.

So much for one side of the fork. On the other side is a different poetic legacy, sponsored by its own theological heavyweights. To be sure, it is still a part of the same ‘tradition’ about Hell that Hart objects to in his work, in the sense that Hell is viewed as a place of eternal conscious torment for the damned. But this other stream places different emphasis on the necessary faith one must have to merit salvation. To an extent, it is conditioned by time and place. Dante and Milton have, however complicatedly, a conviction that some providential synthesis of Church and World has taken place (for the former, in the Holy Roman Empire, and for the latter, in the Cromwellian Protectorate). There is little love lost for the hellbound masses on the basis that God has dramatically shown, through providential guiding, that He alone saves whom He will - it is not of their own merit, after all, that they find themselves to be chosen people, and it comes with grave responsibility. They will surely have to give account, one day, of how they put their supernatural advantage to good use. But what about a poet who writes not from the warm centre of the Christian imperium, but from a ragged monastic outpost at the wild, thin edge of the known universe, threatened daily by marauding Danes. I am speaking here about the Beowulf poet.

Beowulf was an legendary Geat (a near-enough neighbour of Danes and Swedes), and the subject of the first great English epic, written in Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse. The poet, judging from his occasional Christian moralising on the tale he is narrating, is a monk (the only likely candidate for a literate Christian at this period in England), and this presumably causes him a few concerns in a like manner to Dante and Milton, who also have to reckon with a pre-Christian past. In a way, the Beowulf poet (or the final hand on the manuscript - it is impossible to say precisely when the poem was written, and by whom) has no cause to positively reassess the legacy of a roving Scandinavian warrior - Danes frequently plundered monasteries, and terrorised citizens, before finally plucking the English throne from the House of Wessex in 1013, and establishing Danish rule in the personages of Sweyn, and then Cnut. This ended the line of Alfred the Great, a self-consciously Christian monarch who claimed himself as a descendent of Noah. Beowulf is no natural friend of the Christian faith. How little the eternal damnation of a representative of such a godless race would trouble the conscience of St Augustine! And yet, when Beowulf dies after defeating the wealth-hoarding dragon at the end of the poem, the narrator is gracious enough to leave open the possibility of his passing to eternal bliss: Beowulf’s soul goes on to soðfæstra dom - “the judgement of the righteous” (l. 2820).

There is a little ambiguity, of course. Is this a subjective genitive (“judgement at the hands of righteous ones”) or an objective genitive (“judgement passed on those who are righteous”), as Mitchell & Robinson ponder (1998, p. 147). In either case, Beowulf’s pagan world - with its myths and monsters - is finally subsumed within the Christian arc of judgement, and, possibly, redemption. But many 20th century scholars are convinced we have here a very positive take on a virtuous pagan’s eternal fate: “All we can be sure of is that the poet, no theologian, knows that an appreciative God has taken this saint of the heroic world off into some safe place with him, call it what you will” (Irving, 1984, p. 21). I would agree, and Beowulf at large is a good example of the relatively seamless assimilation of heroic, tribal values into an increasingly Christian English culture. The arrival of evangelistic missions there was not, as Bede’s portrait suggested, a sensational clash of civilisations, however much he would have liked it to be. As R. D. Church notes: “The Ecclesiastical History… is a work written by a man who stood outside the world which he described, one who saw that world through the eyes of the biblical exegete” (2008, p. 180). Rather, the battle plan to convert the Angles included premeditated concessions to old customs and localities - Gregory the Great, the Pope who stimulated the Augustinian mission of 597AD, advised an English abbot that they were to use old sites of worship as the new churches, to better appeal to the natives.

How different Beowulf’s fate to Virgil’s! Both are at the mercy of their sympathetic poetic narrators, but only one stands a chance of heaven. I have suggested that such a fond hope for the destiny of heathens, especially when they have proved themselves worthy, was a product of time and place; in Anglo-Saxon England, Christian hegemony would need to be won by degrees, slow change, and absorption. This was not the imperial confidence of Dante, nor the assurance of Providence that animated a Republican Milton. It rather chimes better with an older tradition that we see during the earliest apologetic work of Christians, in the likes of Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Origen, who all lived under the spectre of persecution. They, to better swerve any accusations that Christians were enemies to the Greco-Roman way of life, tried to justify and legitimise their new school by suggesting that, really, Christianity was not something set against the culture per se:

Justin was especially interested in the ties between philosophy and Christianity and impressed by the truths of the Platonists, whom he believed to have most nearly approached Christianity. In fact, he supposed Plato to have been influenced by Moses; (Cindy Vitto, 1989, p. 9)

Logos becomes a lynchpin for this historiographical ‘trick’. Logos meant something to Greek philosophers - the rational principle of the cosmos - but Christians had freighted it with their own meaning: “In the beginning was the Word (logos)”, St John 1:1. For these apologists, both Socrates and Abraham are Christians because they sought the Logos. And here, even the most trenchant Infernalists - those on the other side of the fork I have been sketching out - allowed that the Israelites might have had a kind of ‘implicit faith’. They knew, through the prophets, that Jesus was coming; God’s chosen people could be spared Hell. And with that, a certain principle was sold. If a theologian could wangle the idea that their admired person in a sense cooperated with God by pursuing their reason as far as the revelation they had would allow, then they had surely mustered up a kind of faith, and therefore could be admissible to heaven.

What we see in all this, is another tradition about Hell, and who goes there. At some places and times in Christendom, there has been a greater trend to find common ground, and look for hopeful theological cases to make, that God surely tries to make use of what he can in our lives. A noble warrior like Beowulf displayed good virtues, like courage and honesty, and had given up his life for his people - this was surely enough of a Christological ‘contour’ to his life to suggest he had a kind of Christian faith? The Jews had been given shadows of what was to come - this could surely count as the beginning seed of faith? One can certainly see a tension: how does this not fundamentally denigrate Christ’s role as a unique and final means of salvation tendered to mankind? The theology had to be creative to avoid sanctioning a kind of Pelagianism - that ‘good works’, even those apart from Christ, could merit grace and salvation from God. But they could certainly envy the easier ride that Pelagianism had on the issue of salvation - God’s potentia absoluta made all things possible for Him, to save any that mustered up good works and avoided sin, whether Christian or not.

The Scholastics made good use of ‘implicit faith’ - sometimes to open the gates of heaven, sometimes to exclude (Bonaventure in his Commentary on Lombard’s Sentences for instance used the concept precisely to damn the pagan philosophers, as they had not possessed it, unlike the Hebrews). St Thomas Aquinas can be thought of on this more progressive end I think - in De Veritate he outlines a view that God will never let a good man burn without a really explicit nudge to set him on the right track:

Although it is not within our power to know matters of faith by ourselves alone, still, if we do what we can, that is, follow the guidance of natural reason, God will not withhold from us that which we need… it is likely that the mystery of our redemption was revealed to many Gentiles before Christ’s coming, as is clear from the Sibylline prophecies. (Question XIV, Answer XI).

The idea that God would send an angel was hardly fanciful to someone as steeped as Thomas was in the biblical story. It is of course a convenient escape mechanism - ‘God probably sent an special emissary to bring them up to speed with the Christian faith’. But it was far from a kind of speculative gloss in a dense Scholastic tract. Even in Dante - and in folklore beside - the idea that a pagan might receive a ‘heavenly download’ is displayed rather breathtakingly in the form of the Emperor Trajan. The popular mediaeval stories held that Pope St Gregory the Great, after remembering Trajan’s good deeds, prayed for his salvation, an event which makes it into the Commedia: “the hope /that gave force to the prayers offered God /to resurrect him and convert his will” Paradiso, XX, ll. 109-11. It affects Trajan’s brief resurrection, conversion, and attainment of heaven after his “second death”.

Of course, a few more doctrinal ideas are being presumed here in order to keep this hopeful scene in shot: the jurisdiction of the Church, the efficacy of prayer for the dead etc. They are such that make this second stream rather less palatable to a Reformed sensibility. In any case, it represents, I think, a ‘traditional’ answer to the question of “Am I going to Hell?” that surprises us by leaving a gap for the Divine Mercy, where the unremitting logic of election would snap it shut again. It will be for the reader to judge whether the preservation of that space is acquired in bad faith - through ‘creative theology’, or idle speculation. And that is to be taken seriously - we cannot handwave St Augustine away, even if it is fashionable these days to dismiss him as a neurotic. He sees things with clarity, even if we dislike his conclusions, and cling to an alternate tradition. And the fact that this tradition exists, and can be pointed to in texts throughout Christian history, surely debunks one bien pensant view: that it is only in our oh-so-enlightened times that we dare, even in the face of Hell itself, to pin our hopes on a wideness in God’s mercy. For as Christians since the very beginning have said about that: it’s all we got.